With the arrival of COVID-19, Together Anywhere is asking, what can we learn from history regarding the transience of our humanity and the way we move about space? What are the benefits of our travel? What are the consequences? How might these answers inform us of where we need to go next? In our last post, we explored the beginnings of travel from Native American trails to the missionary settlements. We left off with Oregon Trail settlers waiting for transport down the Columbia River rapids. Some thought maybe they could find another route to Oregon City but there was a giant obstacle in the way. This is where our next story begins.

Stuck at The Dalles with their two separate wagon train parties, the wagon trains led by Sam Barlow and Joel Palmer decided they didn’t want to wait for their transport down the Columbia River rapids. In September of 1845, the two men joined forces and together led 30 wagons through the Cascade Range and towards the southern flank of Mount Hood. Palmer is said to be the first person to climb Mount Hood, ascending to nearly 9000 feet to look for an ideal path around the mountain. However, an ideal path for wagons was not found. As winter set in, the travelers were lacking in food and provisions and were forced to leave their wagons and complete the remaining miles to the valley on foot, arriving in Oregon City on Christmas night three months after departing The Dalles.

Now safe and settled in the valley, Sam Barlow and partner Philip Foster quickly went after entrepreneurial pursuits and informed the territory governance that they had found the perfect path around the mountain. They were granted the right and money to build the Mount Hood Toll Road which became known as the Barlow Road.

During the first year of operation in 1846, over 1000 people and 150 wagons arrived. The new road was rough, steep, and dangerous particularly in sections like Laurel Hill. But it was cheaper and possibly safer than going down the Columbia River rapids. Depending on who you asked, Barlow was either the most loved, or hated, man upon pioneer arrivals to Oregon. During those first years, the men charged $5 per wagon and 10 cents per head of livestock. But with a small profit margin and a difficult to maintain road, both Barlow and Foster abandoned the project and partnership just two years later in 1848. If only they had waited just a bit longer as things were just getting started.

The Oregon Trail popularity boomed with the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 allowing individuals to claim 320 acres of land in the Oregon territory for free, worth over 5 million dollars in today’s terms. At the peak of the Oregon Trail in 1852, over 10,000 people arrived with a quarter of them likely to have traveled down the Barlow Road. By 1860, the population of Oregon had more than quadrupled from ten years before with over 7,000 individuals owning 2.5 million acres of land.

Private owners took care of the Barlow Road and its five different toll gates for the seventy years following Barlow and Foster. And just how significant is it? Early pioneer and politician Justice Matthew P. Deady of the Oregon Territorial Supreme Court said of the trail: “The construction of the Barlow Road contributed more toward the prosperity of the Willamette Valley and the State of Oregon than any other achievement prior to the building of the railways.”

The early settlers like Joel Palmer, Sam Barlow, Philip Foster, Oliver Yocum and many others are responsible for the naming and development of this area. Most of the villages around Mount Hood trace their roots to the homestead and Oregon Trail era, when the first settlers claimed the land. Villages like Zigzag, Faubion, Welches, and Wemme.

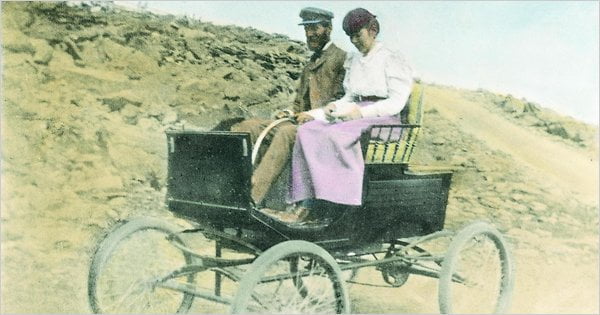

This village of Wemme was named for E. Henry Wemme, a ‘public-spirited citizen’ who arrived in Oregon in 1882 at the young age of 21. Born in England, he managed to travel around Europe working odd jobs despite his limited education before immigrating to the United States at eighteen. When he settled in Portland, Wemme began a long series of business ventures. His first fortune came from a tent and awning business that had considerable success in a time of gold rushes and wars. Then he found wealth in Portland real estate. This once poor immigrant was now quickly becoming one of the richest men in Oregon. Wemme’s true passion for automobiles led him to purchase the first car to arrive in Oregon – an 1899 Stanley Steamer.

At this point in the late 1800s, Mount Hood was buzzing in tourism and recreation. As it was too difficult of a journey for one day, sightseeing carriages pulled by horses would take visitors up the mountain on their multi-day visits as lodges and accommodations made their debut. Before the mass production of automobiles in the early 1900s, taxis, known as motor stages, would transport visitors from Portland to the mountain and back for eight dollars, that’s about equivalent to $250 dollars today.

Henry Wemme recognized the future of transportation was in automobiles. He was a founding member of the Portland Auto Club and was a strong advocate for road building in the Pacific Northwest. It was this passion for transportation by car that led him to become the final individual to purchase the Barlow Road for about $5000 in 1912. Told he only had months to live, Wemme worked quickly to leave a lasting legacy using $25,000 of his own money to improve the road and eliminate the tolls, encouraging more recreation tourism to Mount Hood. Knowing his days were numbered, he tried to donate it to the state of Oregon but it wasn’t accepted, citing that the road was too expensive to maintain.

Interestingly, the state was beginning to pave the Scenic Columbia River Highway at this same time which was the first paved highway in the Pacific Northwest. Highway 35 on the east side of Mount Hood was also in existence but washouts and difficult road conditions were a continuous struggle. However people like Wemme likely wondered: Could it be possible someday to drive around the entire mountain?

Next week we look at the beginning of car travel and the transformation of tourism and recreation in Oregon.