You might know that Crater Lake National Park is Oregon’s only national park, that its namesake lake is the deepest in the United States, and that Rim Drive—the 33-mile loop around the lake—is among the most scenic drives anywhere in the Pacific Northwest.

And while that’s all true, there’s a lot to Crater Lake’s history you might not know—like how the Civilian Conservation Corps shaped the park, the fact that a campground once lined the lake’s rocky rim, and some of the Native American lore that has been passed down since time immemorial. So as you plan your next adventure, here’s a bit of the secret history of Crater Lake National Park.

First, to make it easy, this audio excerpt from the Together Anywhere Driving Tour of Crater Lake National Park briefly tells you all you need to know. We’ve also included a map of the area for a reference to area highlights.

Crater Lake, a sacred place to local Native American tribes

One of our favorite stops along Rim Drive is at Skell Head, which pairs its stunning lake views with an interpretive panel that recounts a story, told originally by the native Makalak people and passed down through their descendants in the Klamath tribe, of how Crater Lake came to be.

The tale begins with the Spirit chief Llao, who lived in the below-world beneath Mount Mazama. On a rare visit to the above-world, he fell in love with Loha, the daughter of a Makalak chief. When she refused his advances, Llao literally lost his cool, rising to the top of the mountain and hurling fire down on the people below. Skell, the Spirit chief of the above-world, stood on nearby Mount Shasta and defended the people as he and Llao engaged in an epic battle. Eventually, Skell drove his adversary back to the below-world—and Mount Mazama soon collapsed in on Llao. The lake that formed in its wake became known to the Klamath people as Giiwas—a sacred place.

That origin story is just one of several the Klamath people have for the creation of Crater Lake—from how Mount Mazama erupted to how the lake filled with water. One legend you won’t see on any interpretive panels during your travels, maintains that Wizard Island is actually the physical head of Llao—and that it only exists today because the monsters of Crater Lake refuse to eat the head of their master.

Those legends show just how significant Mount Mazama has been to Native American tribes since time immemorial.

Following its formation, Crater Lake would become a place where young Klamath and Modoc men sought spiritual guidance on vision quests—a practice upheld today.

Mount Mazama’s eruption was big. Really big.

As you may know, Crater Lake only formed in the wake of Mount Mazama’s violent eruption some 7,700 years ago. But just how massive was Mount Mazama’s big blast?

When it erupted, Mount Mazama sent ash, pumice, and lava racing in every direction. The super-heated avalanches filled valleys, flattened forests, and diverted rivers. In fact, the modern-day Pumice Desert near Crater Lake’s northern entrance was once a rocky ridgeline, festooned with forested slopes—at least, it was until Mount Mazama buried it under 200 feet of ash.

As the eruption unfolded, ash and pumice reached as far as modern-day Alberta, more than 1,000 miles away in Canada. It was, and remains, the largest Cascade Range eruption in the past 1 million years. Yes, you read that right.

Most of Mount Mazama’s magma chambers soon emptied, and the towering peak quickly collapsed in on itself. When the dust settled, just a few days later, a large bowl had been left behind where the mountain once stood. Crater Lake, as we know it, would soon be born in that bowl.

The long-running effort to establish Crater Lake National Park

How did Crater Lake become a national park, anyway? And how different might our beloved park look if not for the efforts of a wide-eyed schoolboy from the Midwest?

To set the scene, I want to take us back to 1885 — when William Gladstone Steel first set eyes on Crater Lake; it was a moment he’d been dreaming about for 15 years, ever since he read about the lake in his local Midwestern newspaper as a schoolboy. After finally seeing the lake in all its glory, Steel remarked: “An overmastering conviction came to me that this wonderful spot must be saved, wild and beautiful, just as it was, for all future generations, and that it was up to me to do something. I then and there had the impression that in some way, I didn’t know how, the lake ought to become a National Park.”

On returning home, he got busy making his new dream come true. Over a ten-year stretch in the late 1800s, Steel wrote one thousand letters to the country’s largest newspapers, urging every editor and postmaster in Oregon to circulate a petition advocating for the park’s protection against commercialization and private ownership. He also wrote a 112-page book called “The Mountains of Oregon” — which he then mailed to President Grover Cleveland, members of the cabinet, and the U.S. Congress.

Remember: In the 1890s, the concept of national parks was still a new idea. Yellowstone National Park had been created just a decade earlier, and no new parks had been established since.

Steel faced stiff opposition in Washington, D.C., where ranchers, prospectors, and timber barons lobbied to derail his dream, while Congress debated the importance of preserving the American West. Three more national parks were established before the turn of the century: Sequoia, Yosemite and Mount Rainier.

Finally, after seventeen years of advocacy, Steel’s dream came true when Crater Lake emerged as the United States’ fifth national park on May 22, 1902.

It’s an impressive sight whenever you visit, but Pumice Castle is especially striking in the afternoon. That’s when the sunlight hits the rock formation head-on—bringing out those vivid hues of orange and red, creating a nice contrast between the grays and browns around it. On a sunny day, the castle is nothing less than regal.

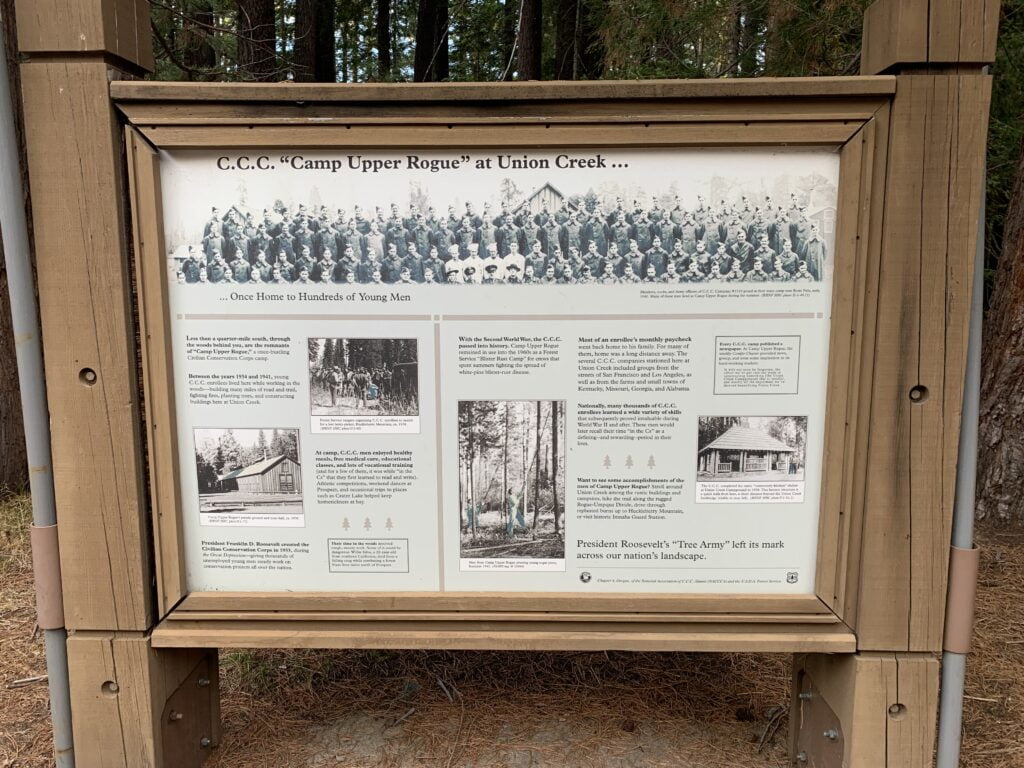

Civilian Conservation Corps shaped the Crater Lake experience

If you’ve ever driven around Crater Lake, hiked its trails, or admired its vistas, you can thank the Civilian Conservation Corps, also known as the CCC. Without the hard work of those young Americans throughout the 1930s and early 1940s, the park might look very different today.

After the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt enacted his famous New Deal in 1933, establishing multiple social service agencies to kickstart the U.S. economy. Similar to the Works Progress Administration, or WPA, the Civilian Conservation Corps was an emergency relief agency helping young people learn new trades while making a little money. In 1933 alone, over 12,000 men worked on 64 projects throughout Oregon—including two at Crater Lake. And by the time it ended, nearly 1,000 workcamps had been established across the United States, providing jobs for over 3 million men.

Between 1933 and 1941, the men spent summers building hiking trails, erecting employee cabins, installing guard rails along Rim Drive, fixing outdated roads, crafting signs and markers for park buildings and landmarks, fighting fires, treating several thousand acres of forests to protect against insects, improving safety at scenic overlooks… You get the idea. They even built a small blacksmith shop at Annie Spring for good measure.

Remarkably, the CCC spent multiple summers working on dozens of landscaping projects around the park. (Yes, landscaping in a national park.) In all, they planted more than 3,000 trees, shrubs, and bushes around Crater Lake Lodge and park buildings; reintroduced native plants to dusty areas that had been ground down by overuse; beautified park campgrounds; installed walkways between buildings; and the list goes on.

Eight years after it arrived, the CCC spent its last summer at Crater Lake in 1941. When the United States entered World War II that December, interest in the program had dried up, young Americans were shipped overseas, and funding was diverted to the war effort. At that point, the CCC had run its course.

Some of the program’s contributions have been lost to history, such as the campground that once sat atop the Crater Lake rim. But many projects still remain visible today, here and throughout Oregon and the entire United States. What CCC works can you spy as you travel through the park?

Want to know way more?

Together Anywhere has created a way to explore Oregon through stories while driving, remaining separate from other travelers as you go down the road, learning more about this beautiful place we get to live. This post is an example of our tours, except our tours speak to you. You just download the app, choose your drive, and you are on your way!

Our tours are ever expanding around Crater Lake, Central Oregon and Oregon at large!

Tour content for Crater Lake National Park and surrounding area by Matthew Wastradowski for Together Anywhere.

One reply on “The secret history of Crater Lake National Park”

Very nice. Been there many times. The name C.L. Stuck in 1869 when the editor of the Jacksonville, Oregon sentinel news, James Sutton, along with 6 others met 4 men from Fort Klamath, Oregon, scaled to the rim, named it “Crater Lake”. Thus the name. James Sutton, son of Sara and John Sutton———-was my grandfather. I am in possession of Sara’s diary of her journey ( 1852 ) over the Oregon trail to Oregon.