COVID-19 has changed the way we move about world. Airplanes are grounded, the cruise ship industry decimated, and buses are empty. People are indoors, using their cars less and they are staying closer to home. Access to travel to the entire world, as it was just prior to COVID-19, has drastically changed. However, when looking at global travel in a historical context, it is a relatively new phenomenon.

Explorers and settlers went to great lengths, often with dire consequences, to bring us to where we are today. And now in this time of change, questions arise. What happens next? At Together Anywhere, we are asking, what can we learn from history regarding the transience of our humanity and the way we move about space? What are the benefits of our travel? What are the consequences? How might these answers inform us of where we need to go next? Well, let’s begin to find out.

What do humans need to travel? Well, basically, we just need feet. Ok, and maybe some good shoes. Did you know that the oldest known footwear in the world was found right here in Oregon? They were found in a cave at Fort Rock in south central Oregon and are now housed at the University of Oregon’s Museum of Natural and Cultural History in Eugene. While written language doesn’t tell us exactly who owned these shoes, some history of a tribal Oregon is known.

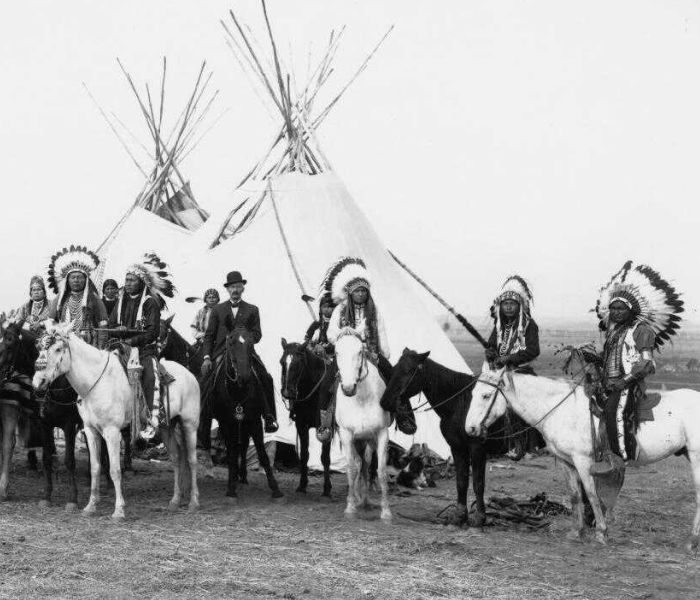

For more than 8,000 years, hundreds of Native American tribes called this area home, like the Multnomah, Kalapuya, Molalla, Clatsop, Clackamas, Tillamook, Wasco, Klamath, Umpqua, and Siletz people to name a few.

It is known that tribal migration occurred seasonally all over Oregon. Many tribes would live nomadically in the lower Cascades and upper river canyons catching fish and hunting game. The Kalapuyans, for example, would then spend their winters in the lower valley in what is known today as the Willamette Valley. The Native tribes thrived in this area as the Willamette Valley is home to 61 species of fish, 250 species of wildlife and thousands of species of plant life. As westward expansion grew in the 18th and 19th centuries, times were unchanging for the valley and its’ original inhabitants as recent as two hundred years ago. But as settlers quickly moved in, the Native tribal migration, fishing practices, and even their existence as a people was drastically altered.

But before we go further into the Native American encounters with the settlers, let’s back up a bit first. When and why did those first outsiders travel to Oregon? Who were they and how did they get here? Surely not by foot. Oregon was first encountered in the late 1500s by Spanish explorers. Globalization and international trade (sound familiar?) were in full swing and explorers were constantly looking for ways to beat out the competition. Spaniard Bruno de Heceta explored the Oregon coast in 1775 and British Captain James Cook is known to have been here in 1778 before meeting his fateful end on the Hawaiian islands.

The first beginnings of the settlement story goes back to 1792 when American explorer captain Robert Gray challenged himself to cross the Columbia Bar, the location where the Columbia River meets the Pacific Ocean near present day Astoria, Oregon. A difficult entrance known worldwide as the “graveyard of the Pacific,” over 2,000 ships have wrecked when trying to cross at this location. Gray is noted as being the first recorded white explorer to be successful in making this attempt in May of 1792.

Six months later, following Gray’s path, British Lieutenant William Broughton was sent by Captain George Vancouver to explore what Gray had named the Columbia River. Broughton made it as far as the Sandy River delta and named the mountain he saw “Hood” after British Admiral Samuel Hood who had never even been to the Pacific Ocean. British exploration maps were created with the name Mount Hood and when Lewis and Clark descended the Columbia River less than 20 years later, they noted “a mountain which we supposed to be mount hood.”

With the Americans and the British staking claim and naming landmarks, the dramatic future and competition for this area was just beginning.

Let’s pick back up to the story of the battle between nations for ownership of the Oregon country, known historically as the Oregon Question. But first, our first question to answer, why is it even called Oregon? Instead of giving a long winded answer of multiple theories, I’ll just tell you the summary: no one really knows. It seems to have caught on in some of the first American maps of the rivers west of the Rocky Mountains and the entire region from present day Colorado to the Pacific Ocean became known as Oregon Country. Before the Americans came into the picture, the British, Spanish, French, and Russian governments were all trying to take hold of the area.

The United States joined the game with Robert Gray’s expedition in 1792 and then things really got going with the travels of Lewis and Clark in 1805 and 1806.

At the beginning of the 19th century, French Canadian, British, and American fur traders, were in pursuit of the riches of the Oregon Country, namely, the pelts of the sea otters, sea lions, and our own state animal, the beaver. In 1810, American tycoon John Jacob Astor commissioned the development of Fort Astoria, known later as Fort George when the British took over control following the War of 1812. Years of confusion and difficulty traversing the land followed but that didn’t stop missionaries from crossing the Rocky Mountains in search of Native people to convert. Jason Lee, a Protestant Christian, started the first mission near present day Salem, Oregon. By 1843, he and other missionaries had convinced others to join them and the first provisional government of the Oregon Country was established.

The Oregon Treaty was signed in 1846 and established the border at 49 degrees latitude between the United States and British North America, now known as Canada. The Oregon Country was now officially part of the United States. Later renamed the Oregon Territory, it encompassed present day Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and parts of Wyoming and Montana. What happened next? One of the largest voluntary land migrations in human history, none other than the Oregon Trail.

Part Two coming next week.

Do you like feeling connected to places you visit? Enjoy stories? We have many out there and more always coming. Download our app on the Apple Store for iOS or the Google Play Store for Android devices. #youradventureisready with Together Anywhere.

One reply on “A history of travel in Oregon – Part One”

[…] travel? What are the consequences? How might these answers inform us of where we need to go next? In our last post, we explored the beginnings of travel from Native American trails to the missionary settlements. We […]